How Do Past Relationships Affect Current Perceptions

In this article I explore attachment theory; maternal deprivation and social isolation; mental representations and working models; patterns of attachment; romantic partners; and resilience. I also include a section for self assessment, recommended books and references.

ATTACHMENT THEORY

The central theme of attachment theory is that primary caregivers who are available and responsive to an infant’s needs allow the child to develop a sense of security. The infant knows that the caregiver is dependable, which creates a secure base for the child to then explore the world.

The theory of attachment was originally developed by John Bowlby (1907 – 1990), a British psychoanalyst who was attempting to understand the intense distress experienced by infants who had been separated from their parents. Bowlby observed that separated infants would go to extraordinary lengths (e.g., crying, clinging, frantically searching) to prevent separation from their parents or to reestablish proximity to a missing parent.

This early development affects us profoundly as this article will explain.

WE NEED MORE THAN FOOD

Harry Harlow’s infamous studies on maternal deprivation and social isolation during the 1950s and 1960s also explored early bonds. In one experiment, newborn rhesus monkeys were separated from their birth mothers and reared by surrogate mothers. The infant monkeys were placed in cages with two wire-monkey mothers. One of the wire monkeys held a bottle from which the infant monkey could obtain nourishment, while the other wire monkey was covered with a soft terry cloth.

While the infant monkeys would go to the wire mother to obtain food, they spent most of their days with the soft cloth mother. When frightened, the baby monkeys would turn to their cloth-covered mother for comfort and security.

COMPROMISING CONNECTION

While this process may seem straightforward, there are some factors that can influence how and when attachments develop, including:

[1] Opportunity for attachment: Children who do not have a primary care figure, such as those raised in orphanages, may fail to develop the sense of trust needed to form an attachment.

[2] Quality caregiving: When caregivers respond quickly and consistently, children learn that they can depend on the people who are responsible for their care, which is the essential foundation for attachment. This is a vital factor.

Gabor Mate has spoken of his childhood trauma, effecting attachment, having been caused by being a jewish newborn at the time of the holocaust. Inevitably the anxiety of his parents was picked-up by the infant who without language or understanding nonetheless responded to the situation and the patterns were learned and fixed in the developing infant.

Bowlby believed that the mental representations or working models (i.e., expectations, beliefs, “rules” or “scripts” for behaving and thinking) that a child holds regarding relationships are a function of his or her caregiving experiences.

RECONNECTING

In his excellent (and personally recommended) book Attachment in Psychotherapy, David J. Wallin makes the point that parenting does not have to be perfect. It needs to be good enough. The process of breaking and remaking connection actually strengthens confidence and belief: things will be OK.

This is probably also true of other relationships, like friendship.

STRANGE SITUATION

Mary Ainsworth’s (1971, 1978) observational study called the strange situation–a laboratory paradigm for studying infant-parent attachment. In the strange situation, 12-month-old infants and their parents are brought to the laboratory and, systematically, separated from and reunited with one another. In the strange situation, most children (i.e., about 60%) behave in the way implied by Bowlby’s “normative” theory. They become upset when the parent leaves the room, but, when he or she returns, they actively seek the parent and are easily comforted by him or her. Children who exhibit this pattern of behavior are often called secure.

Other children (about 20% or less) are ill-at-ease initially, and, upon separation, become extremely distressed. Importantly, when reunited with their parents, these children have a difficult time being soothed, and often exhibit conflicting behaviors that suggest they want to be comforted, but that they also want to “punish” the parent for leaving. These children are often called anxious-resistant.

The third pattern of attachment that Ainsworth and her colleagues documented is called avoidant. Avoidant children (about 20%) don’t appear too distressed by the separation, and, upon reunion, actively avoid seeking contact with their parent, sometimes turning their attention to play objects on the laboratory floor.

See video here

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QTsewNrHUHU

THE KEY PATTERNS

Others have gone on to explore four patterns of attachment,

Ambivalent attachment: These children become very distressed when a parent leaves. Ambivalent attachment style is considered uncommon, affecting an estimated 7–15% of U.S. children. As a result of poor parental availability, these children cannot depend on their primary caregiver to be there when they need them.

Avoidant attachment: Children with an avoidant attachment tend to avoid parents or caregivers, showing no preference between a caregiver and a complete stranger. This attachment style might be a result of abusive or neglectful caregivers. Children who are punished for relying on a caregiver will learn to avoid seeking help in the future.

Disorganized attachment: These children display a confusing mix of behavior, seeming disoriented, dazed, or confused. They may avoid or resist the parent. Lack of a clear attachment pattern is likely linked to inconsistent caregiver behavior. In such cases, parents may serve as both a source of comfort and fear, leading to disorganized behavior.

Secure attachment: Children who can depend on their caregivers show distress when separated and joy when reunited. Although the child may be upset, they feel assured that the caregiver will return. When frightened, securely attached children are comfortable seeking reassurance from caregivers.

MORE THAN FOUR

Throughout my reading on the subject I have seen variations in the classifications and the terminology used. It seems to be that there are more than just four patterns to cover the following.

*Ambivalent Attachment

*Anxious-Resistant Attachment

*Avoidant Attachment

*Disorganized Attachment

*Secure Attachment

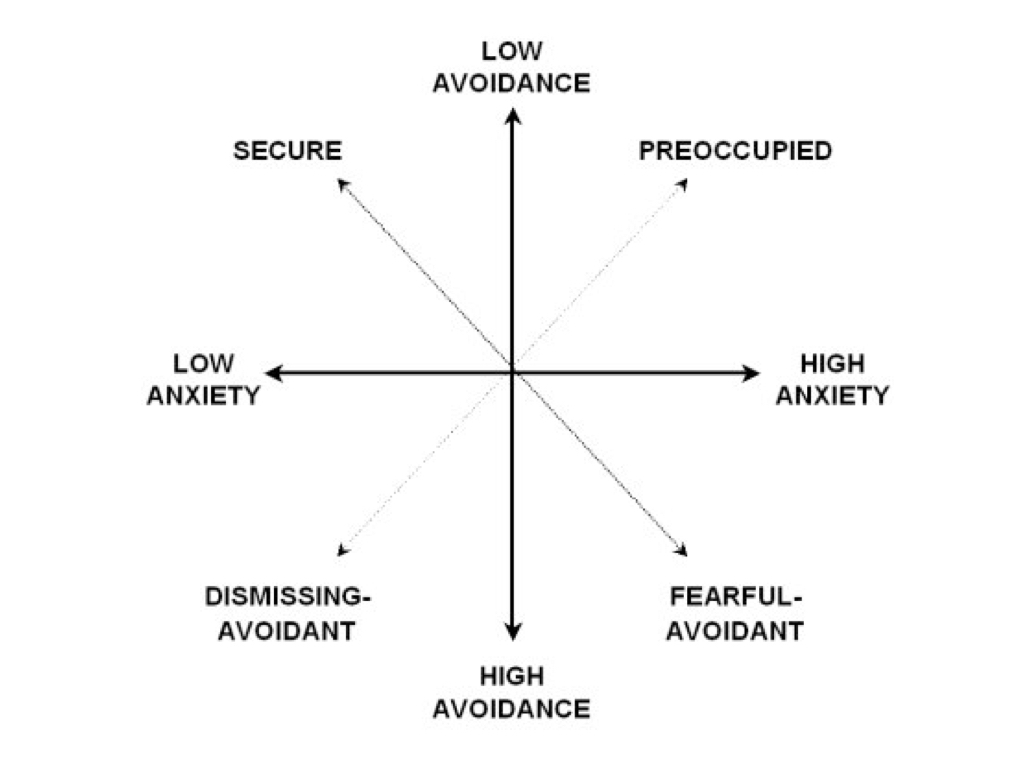

Brennan, Clark, & Shaver, 1998) suggested that there are two fundamental dimensions with respect to adult attachment patterns One critical variable has been labeled attachment-related anxiety. People who score high on this variable tend to worry whether their partner is available, responsive, attentive, etc. People who score on the low end of this variable are more secure in the perceived responsiveness of their partners. The other critical variable is called attachment-related avoidance.

FOR OUR WHOLE LIVES

Attachment theory was extended to adult romantic relationships in the late 1980s by Cindy Hazan and Phillip Shaver. Four styles of attachment have been identified in adults: secure, anxious-preoccupied, dismissive-avoidant and fearful-avoidant.

We may expect some adults, for example, to be secure in their relationships–to feel confident that their partners will be there for them when needed, and open to depending on others and having others depend on them. We should expect other adults, in contrast, to be insecure in their relationships.

For example, some insecure adults may be anxious-resistant: they worry that others may not love them completely, and be easily frustrated or angered when their attachment needs go unmet. Others may be avoidant: they may appear not to care too much about close relationships, and may prefer not to be too dependent upon other people or to have others be too dependent upon them.

WHAT IS LOVE

According to Hazan and Shaver, the emotional bond that develops between adult romantic partners is partly a function of the same motivational system–the attachment behavioral system–that gives rise to the emotional bond between infants and their caregivers. Hazan and Shaver noted that the relationship between infants and caregivers and the relationship between adult romantic partners share the following features:

*both feel safe when the other is nearby and responsive

*both engage in close, intimate, bodily contact

*both feel insecure when the other is inaccessible

*both share discoveries with one another

*both play with one another’s facial features and exhibit a mutual fascination and preoccupation with one another

*both engage in “baby talk”

On the basis of these parallels, Hazan and Shaver argued that adult romantic relationships, like infant-caregiver relationships, are attachments, and that romantic love is a property of the attachment behavioral system

ADULT ATTACHMENT INTERVIEW

Beginning in the 1970s and throughout the ’80s, Mary Main–a research psychologist at the University of California, Berkeley–began interviewing parents and studying their interactions with their babies.

In the study, they found that attachment rejection or trauma in a mother’s childhood was systematically related to the same sort of attachment issues between her and her child. From this kind of attachment research, Main and her colleagues devised an interview method—the Adult Attachment Interview (AAI).

This interview contained 20 open-ended questions about people’s recollections of their own childhood, including:

*Describe your relationship with your parents.

*Think of five adjectives that reflect your relationship with your mother.

*What’s the first time you remember being separated from your parents?

*Did you ever feel rejected?

*Did you experience the loss of someone close to you?

*How do you think your experience affected your adult personality?

OUR LIFE EXPERIENCE

Despite the attractiveness of secure qualities, not all adults are paired with secure partners. Some evidence suggests that people end up in relationships with partners who confirm their existing beliefs about attachment relationships (Frazier et al., 1997).

Secure adults are more likely than insecure adults to seek support from their partners when distressed. Furthermore, they are more likely to provide support to their distressed partners (e.g., Simpson et al., 1992). Insecure individuals make concerning their partner’s behavior during and following relational conflicts exacerbate, rather than alleviate, their insecurities (e.g., Simpson et al., 1996).

If only 55% of us had “secure attachment” as infants, according to research. This should worry us because the other 45% of us suffer “insecure attachment.” That means 45% of us have trouble with committed relationships. It starts to explain why we’ve got a 50% divorce rate,

ADVERSE CHILDHOOD EXPERIENCES (ACE) STUDY

The 1998 Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study showed that 64-67% of 17,421 middle class subjects had one or more types of childhood trauma, and 38-42% had two or more types. In less privileged populations, these numbers are far higher. A national average of all economic groups would likely show 50% or more suffer ACE trauma.

The ACE Study lists physical and sexual abuse and 8 other types, including traumas that happen to newborns like physical and emotional neglect. Such trauma puts children into “fight-flight,” a chronic state proven to shut down the organism’s capacity for feelings of attachment and love. Think soldier in a battle, ramped up in “fight-flight”– he’s not into love.

Half of us are in serious emotional health and medical trouble, and don’t even know it. Interestingly Coaching provides a safe and trusting environment of acceptance which can help create new patters, new behaviours and lasting change for many.

SELF ASSESSMENT

Hazan and Shaver asked research subjects to read the three paragraphs listed below, and indicate which paragraph best characterized the way they think, feel, and behave in close relationships:

A. I am somewhat uncomfortable being close to others; I find it difficult to trust them completely, difficult to allow myself to depend on them. I am nervous when anyone gets too close, and often, others want me to be more intimate than I feel comfortable being.

B. I find it relatively easy to get close to others and am comfortable depending on them and having them depend on me. I don’t worry about being abandoned or about someone getting too close to me.

C. I find that others are reluctant to get as close as I would like. I often worry that my partner doesn’t really love me or won’t want to stay with me. I want to get very close to my partner, and this sometimes scares people away.

Based on this three-category measure, Hazan and Shaver found that the distribution of categories was similar to that observed in infancy. In other words, about 60% of adults classified themselves as secure (paragraph B), about 20% described themselves as avoidant (paragraph A), and about 20% described themselves as anxious-resistant (paragraph C).

Click here to take an on-line quiz designed to determine your attachment style based on these two dimensions.

http://www.web-research-design.net/cgi-bin/crq/crq.pl

Click here to learn more about self-report measures of individual differences in adult attachment.

http://labs.psychology.illinois.edu/~rcfraley/measures/measures.html

Click here to take an on-line quiz designed to assess the similarity between your attachment styles with different people in your life.

https://www.yourpersonality.net/relstructures/

Note the above links are to someone else’s website. We do not see or control the data.

EVERY DAY APPLICATION

We may logically say that if patterns of attachment affect our relationships with caregivers and family (initially as a child, then as a partner and later as a parent) then it seems reasonable to suppose that patterns of attachment affect other relationships, including friends and colleagues. Perhaps patterns of attachment hold clues to community, belonging, purpose or faith?

RESILIENCE

Although some avoidant adults, often called fearfully-avoidant adults, are poorly adjusted despite their defensive nature, others, often called dismissing-avoidant adults, are able to use defensive strategies in an adaptive way.

For example, in an experimental task in which adults were instructed to discuss losing their partner, Fraley and Shaver (1997) found that dismissing individuals (i.e., individuals who are high on the dimension of attachment-related avoidance but low on the dimension of attachment-related anxiety) were just as physiologically distressed (as assessed by skin conductance measures) as other individuals. When instructed to suppress their thoughts and feelings, however, dismissing individuals were able to do so effectively. That is, they could deactivate their physiological arousal to some degree and minimize the attention they paid to attachment-related thoughts. Fearfully-avoidant individuals were not as successful in suppressing their emotions.

David J. Wallin used the phrase Dismissing-Attachment will deal and not feel and Preoccupied-Attachment will feel and not deal with the issues

Chris Fraley believes we still don’t have a strong understanding of the precise factors that may change a person’s attachment style. In the interest of improving people’s lives, it will be necessary to learn more about the factors that promote attachment security and relational well-being.

My own view, expressed above, is that we can modify our attachment style based on new experience and in a safe, nurturing and supportive environment. It may take time to unlearn deeply embedded experience and set new patterns, but it seems to me that there are lessons to be learned from the treatment of trauma, and PTSD in particular, that can be used in a coaching, a therapeutic environment or a stable relationship of positive regard.

CONTACT

tim@thinkingfeelingbeing.com

http://thinkingfeelingbeing.com/

REFERENCES USED IN THIS TEXT

http://labs.psychology.illinois.edu/~rcfraley/attachment.htm

https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-attachment-theory-2795337

https://www.psychotherapynetworker.org/blog/details/17/the-adult-attachment-interview-how-it-changed-attachment

https://www.iasa-dmm.org/about-attachment/Adult-Assessment-Attachment/

https://attachmentdisorderhealing.com/adult-attachment-interview-aai-mary-main1/

RECOMENDED BOOKS

Adult Attachment: A Concise Introduction to Theory and Research 1st Edition by Omri Gillath, Gery C. Karantzas, R. Chris Fraley

Attachment in Psychotherapy, by David J. Wallin