Dismissive-Avoidant Attachment Compared to Autism

I was recently reading about the Dismissive Avoidance Attachment style and was struck by a description that closely resembled some of the behaviours sometimes seen in autism. This has caused me to revisit my reading on attachment styles, which I have shared here.

Dismissive-avoidant attachment is a term for when someone tries to avoid emotional connection, attachment, and closeness to other people. This is not the same as autism, but I can see how it might look the same externally.

Autism, or autism spectrum disorder (ASD), refers to a broad range of conditions characterized by challenges with social skills, repetitive behaviours, speech and nonverbal communication. Social skills development for people with autism involves:

• Direct or explicit instruction and “teachable moments” with practice in realistic settings

• Focus on timing and attention

• Support for enhancing communication and sensory integration

• Learning behaviour’s that predict important social outcomes like friendship and happiness

• A way to build up cognitive and language skills

Dismissive-Avoidant Attachment

Dismissive-avoidant attachment is a term for when someone tries to avoid emotional connection, attachment, and closeness to other people.

People who are dismissive-avoidant are generally very self-sufficient, Dismissive-avoidant behaviours can include “independence to an extreme, not asking for help, setting a lot of boundaries, withdrawing from their partner when getting too close.” People who are dismissive avoidant are often secretive and rigid, not allowing their own plans to be influenced by others and often, not even disclosing those plans at all.

Dismissive-avoidant person avoid any feelings of closeness on others, and don’t offer others the opportunity to feel close to them. Partners, friends, and family members of someone with a dismissive-avoidant attachment style also may not have their needs met in the relationship. In general, people feel safer when they feel connected to others. This isn’t necessarily the case for someone with dismissive avoidant attachment; they might feel safer the more distance they create.

Why?

Because attachment theory is based on how we interacted with parents and caregivers in our youth, it makes sense that the causes of this attachment style can be traced back to young age.

It’s believed that dismissive-avoidant attachment occurs because a baby or small child doesn’t get the attention or care they need from their parents or caregivers. In turn, the infant or child learns that expressing their needs doesn’t guarantee that they will be taken care of.

When a child’s needs aren’t properly met by their caregivers, they may develop the sense that other people can’t properly care for them. That can make someone, even a small child, feel like they have to be self-reliant in order to get what they need in life.

Adding the impact of life’s experiences

When a child is exposed to overwhelming stress and their caregiver does not help reduce this stress, or is the cause of the stress, the child experiences developmental trauma. Most clinicians are familiar with the term Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), but the vast majority of traumatised children will not develop PTSD. Instead, they are at risk for a host of complex emotional, cognitive and physical illnesses that last throughout their lives.

Developmental traumas are also called Adverse Childhood Experiences. These are chronic traumas such as having a parent with mental illness or substance abuse, losing a parent due to divorce, abandonment or incarceration, witnessing domestic violence, not feeling loved or that the family is close, or not having enough food or clean clothing, as well as direct verbal, physical or sexual abuse. The impact of these traumas has been researched extensively. One such body of evidence comes from a database of over fifteen thousand adults, in a now-famous study known as the Adverse Childhood Events (ACE) study.

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) are stressful events occurring in childhood including

1. domestic violence

2. parental abandonment through separation or divorce

3. a parent with a mental health condition

4. being the victim of abuse (physical, sexual and/or emotional)

5. being the victim of neglect (physical and emotional)

6. a member of the household being in prison

7. growing up in a household in which there are adults experiencing alcohol and drug use problems.

An ACE survey with adults in Wales found that compared to people with no ACEs, those with 4 or more ACEs are more likely to

1. have been in prison

2. develop heart disease

3. frequently visit the GP

4. develop type 2 diabetes

5. have committed violence in the last 12 months

6. have health-harming behaviours (high-risk drinking, smoking, drug use).

When children are exposed to adverse and stressful experiences, it can have a long-lasting impact on their ability to think, interact with others and on their learning.

ACEs should not be seen as someone’s destiny. There is much that can be done to offer hope and build resilience in children, young people and adults who have experienced adversity in early life

Growing up to adulthood and beyond

The Dynamic-Maturational Model of Attachment and Adaptation (DMM) emphasizes the dynamic interaction of the maturation of the human organism, across the lifespan, with the contexts in which maturational possibilities are used to protect the self, reproduce, and protect one’s progeny.

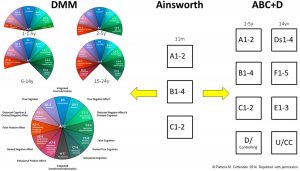

ABCD and DMM classification systems. This figure is a visual representation of the development of the ABCD and DMM classification systems from Mary Ainsworth’s original work with 11-month-old infants, where she identified three patterns of attachment: A, B, and C (see middle section). Main and Solomon (1986, 1990) subsequently extended Ainsworth’s work by developing the ABCD model (see right-hand side). Patricia Crittenden (Crittenden, 1999) subsequently extended Mary Ainsworth’s work by developing the DMM model

In infancy and the preschool years:

A1-2 = Group A, anxious-avoidant attachment;

B1-4 = Group B, secure attachment;

C1-2 = Group C, anxious-ambivalent/resistant attachment;

D/controlling = disorganized/controlling (also known as disorganized/disoriented or just as disorganized).

In late adolescence, and adulthood:

Ds1-4 = Dismissing attachment;

F1-5 = Secure;

E1-3 = Preoccupied;

U/CC = Unresolved state of mind/cannot classify (also known as disorganized/unresolved state of mind or cannot classify).

It seems obvious that we are shaped by our lived experiences, but the challenge may be that in the developmental period from age 0 to 20 this is more significant than an event which may be forgotten but actually impacts the neurological development of the brain, ostensibly hard wiring our perceptions, predilections and propensities.

Reversing this is not impossible, but it is much harder to change a pattern or perception or behaviour which is hard-wired and, in that sense, does seem to share something in common with autism.

Resources and References

What Is Attachment Theory?

https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-attachment-theory-2795337

Social Skills and Autism

https://www.autismspeaks.org/social-skills-and-autism

What Is Dismissive-Avoidant Attachment?

https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-dismissive-avoidant-attachment-5218213

Types of Attachment Styles and What They Mean

https://www.healthline.com/health/parenting/types-of-attachment

The Dynamic-Maturational Model of Attachment and Adaptation (DMM) https://familyrelationsinstitute.org/dmm-model/

Attachment Patterns in Children and Adolescents

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.582688/full

What is Developmental Trauma / ACEs?

https://www.porticonetwork.ca/web/childhood-trauma-toolkit/developmental-trauma/what-is-developmental-trauma

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs)

http://www.healthscotland.scot/population-groups/children/adverse-childhood-experiences-aces/overview-of-aces