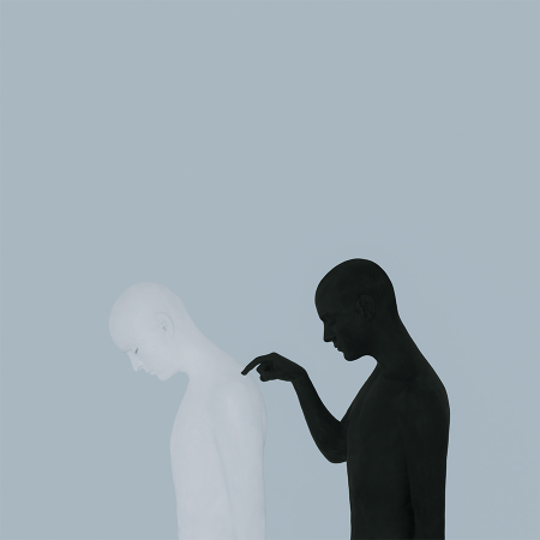

The paradox of organizations and individuals who claim to uphold the highest moral standards but often fall short is both fascinating and troubling. It touches on deep psychological and social dynamics that have been explored by thinkers like Carl Jung, who introduced the concept of the “shadow,” referring to the darker, unconscious parts of our personalities that we might not even be aware of or are unwilling to acknowledge.

One possible explanation for this phenomenon is that the more someone or an organization publicly commits to a set of high moral standards, the more they might suppress or deny their flaws, weaknesses, or darker impulses. This suppression can lead to a kind of psychological pressure cooker where these unacknowledged parts of themselves eventually manifest in destructive or unethical behavior. When these darker aspects are not integrated or dealt with consciously, they can emerge in harmful ways.

Another factor could be the power and authority that often come with positions of moral leadership. Power has a well-documented tendency to corrupt, and those in positions of authority may begin to feel invincible or beyond the rules they set for others. The greater the power, the greater the temptation to abuse it, especially when accountability mechanisms are weak or non-existent.

There’s also a social dimension to consider. Organizations and individuals that position themselves as moral authorities may attract followers or members who are seeking clear, definitive guidance on what is right and wrong. This dynamic can create environments where dissent or questioning is discouraged, leading to an unhealthy culture of secrecy and denial. In such environments, unethical behavior can fester unnoticed or unchallenged for long periods.

Research on moral licensing also offers some insights. Moral licensing suggests that when people feel they’ve done something good, they may feel licensed to do something bad afterward, as if their good deeds have given them a pass. In organizations, this might translate into leaders feeling justified in cutting ethical corners because of their previous good actions or the overall good they believe they are doing.

This topic is explored in various studies and books. For instance, “Mistakes Were Made (But Not by Me)” by Carol Tavris and Elliot Aronson delves into how people justify harmful behaviors and decisions, often without realizing it. There’s also extensive psychological research on cognitive dissonance, which explains how people rationalize actions that conflict with their self-image as moral beings.

In summary, the gap between professed values and actual behavior can be attributed to a combination of psychological denial, the corrupting influence of power, social dynamics within organizations, and the complex ways in which people justify their actions. Understanding these factors can help in creating environments where ethical behavior is more than just a public stance—it’s a lived reality.

NOTES

“Mistakes Were Made (But Not by Me)” by Carol Tavris and Elliot Aronson explores how people justify harmful behaviors and decisions through a psychological process known as cognitive dissonance. The authors explain that when people’s actions conflict with their beliefs or self-image, they experience discomfort (cognitive dissonance). To reduce this discomfort, they often rationalize their behavior, convincing themselves that their actions were justified or that the situation wasn’t as bad as it seems. This self-justification allows people to avoid feeling guilty or responsible for their mistakes, even when those mistakes cause harm. The book highlights how this process happens unconsciously, leading people to persist in harmful behavior and poor decision-making.